The Death and Life of the Great Hoosier Streetcar from 1955-1960

a Case Study of Fountain Square, Indianapolis, Indiana

ABSTRACT

Across the United States in the early days of public transportation, streetcars transported people across cities as they were expanding in area and population. Streetcars provided the city of Indianapolis, Indiana with an efficient transportation system in the early 20th century, but were replaced with buses around the middle of the century. Streetcars were the source of much development across the city of Indianapolis, Indiana and created multiple “streetcar suburbs” that flourished from the invention of the streetcar. Fountain Square, a neighborhood in Indianapolis, was created because of the invention of the streetcar as it provided transportation to and from the city and allowed people to live in a suburb to escape the traffic and bustle of the big city. This study investigates how streetcars operated in Indianapolis from 1955 to 1965 and how they declined with the rise of the bus. Data was gathered from historical newspapers from the years 1955 to 1965 in Indianapolis, Indiana. Results show that during the streetcar era, streetcars in Indianapolis had high ridership and provided transit all over the city. When the streetcar was replaced by the bus system, ridership decreased, traffic became heavier, and the city became more auto-centric. With the downfall of the streetcar came the downfall of public transportation, overall ridership, community fabric, and streetcar suburbs including Fountain Square.

INTRODUCTION

Transportation is an integral component in every city. It fuels development, increases population, and connects cities for great trade and economic prosperity. The city of Indianapolis thrived throughout the 20th century from the use of streetcars through its dense mixed-use center, which allowed people to get to work, shops, and travel to and from home. Indianapolis had different forms of transportation during this era, starting with the mule car and graduating to the autobus by the late 1950s.

The trolley, or electric streetcar, moved on tracks and a wire overhead and could seat 40 passengers each. This made them efficient in providing transportation to a large population of people on a large web of interconnected lines that reached every corner of the city. These trolleys ran from 1890 to 1953. The streetcar connected the entire city of Indianapolis with a vast map of service.

In the early 1950s, the streetcar system in Indianapolis, and across the country, began to decline due to the rise of the automobile and urban sprawl. The decline began with a decrease in service and streetcar lines due to low ridership and led to tracks being ripped out across the city to make room for larger roads designed for the automobile. The rise of the automobile caused the city limits to sprawl, and people began to leave the center of the city and into the suburbs of the city, which led to fewer people using the existing streetcar lines. The decreased ridership led to the streetcars producing less income, and this led to its ultimate decline. The decline of the streetcar was also escalated by the car owners of Indianapolis who desired roads that were car-oriented and free of tracks and streetcars as they were inconvenient for them. As the streetcar declined, it was replaced by the autobus. The bus system did not have the ridership that the transportation leaders planned for and therefore was not as successful as the streetcar. It also did not have the amount of service the streetcar did.

The city of Indianapolis can attribute its vast growth and development to the streetcar system. However, when it was replaced by the bus, the streetcar was completely removed and never utilized again. This study presents an analysis of the impact that streetcars had on the city of Indianapolis between the years 1955 to 1960 and examines its downfall.

METHODS

A qualitative historical research method was used to find data for the use of streetcars in the city of Indianapolis from 1955 to 1960, after the Second World War when transportation became a vital necessity. Streetcars were highly used in the early 1950s, but began to decline in the middle of the 1950s and were replaced with the autobus and personal automobiles by 1960.

Newspaper articles were the primary source of data collection, which were gathered from historical newspaper archives. The newspaper articles provided real-time data and information on any event involving streetcars and included facts and opinions from journalists and residents of the city of Indianapolis. It also compared the transportation system in Indianapolis to the transportation systems of other cities around the country and the world during the same time.

In addition to newspaper articles, journals and maps were used to gather insight from residents and professionals from the city and to see exactly how the streetcar ran in the city. These articles provided modern knowledge and education for issues that happened in the past. The ability to apply current planning and transportation concepts to post-World War II era transportation is good in understanding the quality of transportation then.

DISCUSSION

Streetcar history

Public transportation flourished across the country in the late 1800s in an effort to transport people around cities as they grew. Indianapolis has had three types of passenger transportation throughout its history in the 19th and 20th centuries, including the mule car, streetcar, and trackless trolley.

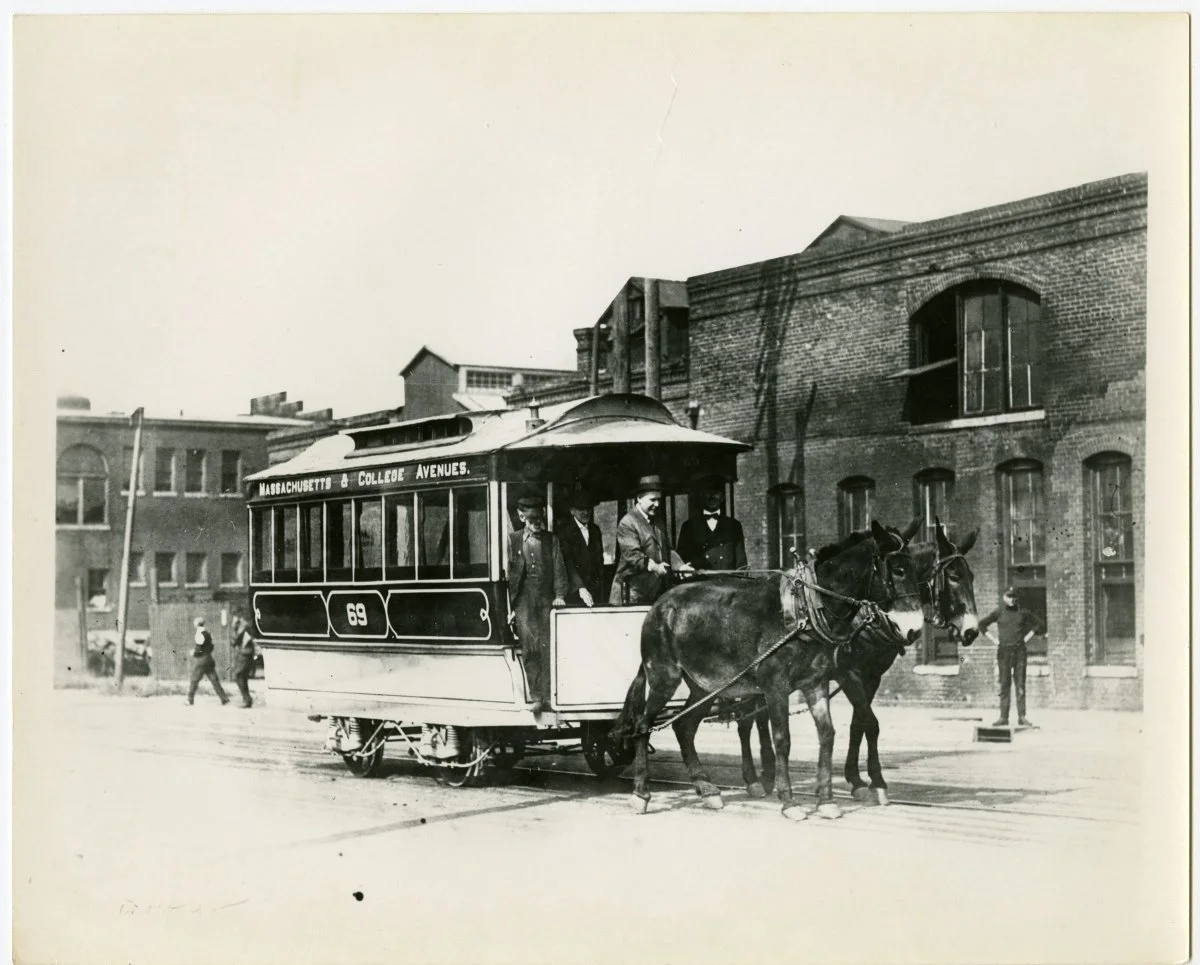

The mule car, shown in Figure 1, and was a 14-passenger vehicle pulled by mules and was used from the middle of the 19th century to the beginning of the 1890s. In 1890, the mule car system was strong with 260 cars and 1100 mules. There were several drawbacks to the mule-drawn trolleys. Because the mules required rest and feeding, they would often have to be changed out which slowed down transportation time. It was also more expensive for this mode of transportation because of the large amounts of food that the mules required. The transportation time was also hindered by the small cars because mules needed lighter cars in order to be able to carry them, so it only sat very few people compared to later modes of transportation.

Figure 1: Mule Car in Indianapolis

Figure 2: Streetcar Map

Figure 3: Streetcar and Its Conductors in 1895

Figure 4: Indiana Interurban Map

Figure 5: Indiana Transit System, Inc. Advertisement

Figure 6: Discontinued Streetcars- Old Trolleys Never Die

Figure 7: Industrialization and Progress Killed the Streetcar

The mule cars in the late 19th century provided good transportation, but people started to require faster transportation between cities. This need, and the invention of electricity, led to the beginning of the electric streetcar. The trolley or electric streetcar moved on tracks and a wire overhead and could seat 40 passengers each as shown in Figure 3. These trolleys ran from 1890 to 1953. The streetcar was designed to move people throughout the city with more frequent stops and lower speeds. The first streetcar system in Indiana was in South Bend in 1888 and by 1895, most major cities across Indiana established a streetcar system that ran until 1953. There were 6 major transportation companies in Indiana: THI&E, Indiana Union Traction Company, Indiana Service Corporation, Public Service Company of Indiana, and the Marion & Bluffton Traction Company. Streetcars in Indianapolis started running in the early 1890s and served about 40 passengers per car. At the streetcar’s height, they transported over 120 million passengers per year from the west side of Indianapolis to Irvington at its eastern point. The level of service provided within the city is shown in Figure 2.

They began to become less popular after World War I, carrying only 52.9 million passengers per year, when cars began to be made, but became more popular during World War II because of the need to ration gasoline. After the decline of the streetcar after World War I, the transit company invested $8 million into the system to get new vehicles and ridership began to improve. This system was also well used during World War II due to gas rationing. During and immediately after WWII, Indianapolis streetcars carried 70 million passengers per year, and ran more than 400 vehicles daily, spanning over 40,000 miles per day. After World War II, personal automobiles and gas-powered buses led to the last decline and death of the streetcar in Indianapolis.

The decline of the streetcar led to America connecting cities to the rural landscape and agriculture boomed. Interurbans were provided for the commuter population and connected cities around Indiana with high-speed trains. “Indiana had one of the earliest and most extensive systems in the country by which the capital city was connected with every other part of the state … long before World War I.” What made the interurban so effective was that it transported between cities, and then connected with the local streetcar lines to transport passengers within the city. The first interurban line ran south from Indianapolis to Franklin. This line was successful and carried over 300,000 people during the first year. The second line in Indiana connected Indianapolis to Greenfield. The interurban system in Indiana provided consistent service “10 to 12 trains per day between the major cities.” Indianapolis became connected via over 2,400 miles of tracks to other major cities around the state, including Lafayette, Kokomo, Muncie, New Castle, Richmond, Connersville, Greensburg, Beech Grove, Louisville, Martinsville, Terre Haute, Danville, and Crawfordsville. The interurban system in Indiana was one of the largest and most connective systems in the country at the time, and its . The Traction Terminal in Indianapolis was the largest in the country with 9 floors. “Lines radiated from Indianapolis to Fort Wayne, Louisville, Lafayette, Peru, Terre Haute, and Richmond (and six other routes). These interurbans then connected with others, reaching Chicago, Toledo, Columbus, and even farther.” These interurban cars ran slower in the city centers and went fast through the countryside. Interurbans started popping up across the country, and you could ride an interurban from Sheboygan, Wisconsin to Albany, New York. The interurban system allowed Indianapolis to be connected to its metropolitan area with its expansive service area diagrammed in Figure 4, for ease of transportation of employees, visitors, and residents. The interurban was negatively impacted by the Great Depression and the rise of the personal automobile.

The streetcar as a convenience

The streetcar system in Indianapolis was a necessary service for the city and its residents. It transported people to and from a destination. The Indianapolis Transit System carried around 60,000 passengers a day, while downtown Indianapolis only has around 14,000 spots in the mile square, so transit is needed because downtown cannot handle everyone driving instead of riding public transportation. Though the transit system in Indianapolis was not profiting, there was still a large need for public transit in Indianapolis. An Indianapolis News article said that “during the first six months of 1955, for instance, a total of 23,228,991 passengers were carried! That’s a daily average of 128,337 passengers!”

The streetcar provides an inexpensive way of moving around the city and serves as a financial relief that a personal automobile cannot provide, proven by the newspaper ad in Figure 5. Riding public transportation saves money on gas, parking, car insurance, and car maintenance. For 20 cents in 1955, or $2.17 in 2022, the transit will take you across zones, and for 15 cents in 1955, or $1.62 in 2022, it will take you anywhere within a zone. In 1955, the Indianapolis Transit System made a change that fares were charged for the length of ride, so the closer to the city you live, the cheaper your fare is. There was also an express service to cut down the time spent on the trolley or bus for those living further away. “Public transportation is always tailored to the use to which you put it. More riders, more service; fewer riders, less service.” Those who use transit are only charged when they use it, and it is not a constant rate, which saves money in the long run. Not only does the streetcar save you money while using it, but it also increases real estate values as it is an amenity that is available to the homeowner, but does not cost anything to live by it. The streetcar is attributed to creating walkable, mixed-use streets with increased property values and desirability because of their walkable streets designed before the “Sputnik era.”

Public transit offers cities more than just transportation for residents and visitors, it provides an opportunity to enhance the economy. “Access to transportation is essential for upward-bound mobility.” The transit system also employed people and brought people to and from businesses and work, which stimulated the economy and supported local businesses.

Public transportation is a faster way to get from location to location because it allows the passenger to avoid finding parking, and in efficient systems, it is in a separate lane to avoid automobile traffic. Separating the transit from car traffic proved successful in Nashville, Tennessee. The Indianapolis News said that transit in Nashville “is different than other transit systems around the country because the bus has a designated lane during rush hours, which allows it to be on time and consistent for its riders.”

Streetcars and other public transit provide amenities for the community aside from convenient and inexpensive transportation, including shelter accessibility, air conditioning, and comfortable seats. The stations protect riders from the weather because they are covered. They provide amenities such as strollers, free rides for kids and church-goers on holidays, and accommodating the elderly. Using more types of transportation in popular places makes it more accessible for all people and reduces the parking needs for that space.

Though automobiles were beginning to become popular among the general population, the transit system found a way to encourage drivers to also use the bus by providing parking lots to park and ride public transportation. The concept was that if you do not live by a transit station, you can drive to one and ride transit into the city center to cut back on time and money spent with a personal car.

Streetcar as a social institution

Streetcars acted as a place of education, a social club, and a way to get people where they need to go. During its prime, streetcars transported tens of thousands of passengers per day, and people saved over 240 hours of time per year riding without sitting in automobile traffic. This made the streetcar a place for socialization among its passengers. People could talk, read newspapers, and listen to others' conversations. Not only was this socialization for its passengers, but it was also the “poor man’s college on wheels” or a place of education. The streetcar was a space where people read newspapers over others’ shoulders, learned of the news by word of mouth and listened to the viewpoints of others. The use of the streetcar also encouraged people to socialize on the streets and during this time, there were many people walking on the streets and sidewalks to get to and fro, which improved safety in these areas.

Streetcars also required their passengers to exercise each day by walking or running to the streetcar stop and to the final destination.

The streetcar is known to many people as a memory and was a large part of people’s lives. These streetcars provided transportation to and from important events or everyday necessities for so many residents of Indianapolis during the first half of the 20th century, so many memories are attached to this mode of transportation. The Indianapolis Star provides a great tribute to the streetcar- “A mode of transportation that faded from the Hoosier scene and is almost forgotten is the interurban system with its electrically propelled cars and little waiting stations spotted over the countryside.” The Indianapolis News reported on people reminiscing on their experiences on the streetcar and how the streetcar took them to places that give them fond memories. “Ah the picnics, the tennis games, the good times at Fairview.”

As much as streetcars had positive effects on society, the streetcar also became a place of contention with racial inequalities. Transportation in the 1950s was the beginning of the displacement of black people around the country, as white families were able to move to the suburbs and ride their cars to work, while black families were forced to ride public transportation. This caused decreased ridership in the center of the city because of decreased population and ultimately led to the decline of the streetcar, as streetcars were only used in densely populated areas of downtown Indianapolis. Transit companies in the south were being urged to desegregate their transportation but were not required. In some places, going against the desegregation laws was criminally punished.

The downfall of streetcars in Indianapolis

Transit strikes

The beginning of the end for the streetcar began in the early 1950s with nationwide strikes due to fare increases and no wage increases. Indianapolis had a transit strike in 1954 that affected wait times for passengers and impacted their way of transportation to get to work or other destinations. In 1955 alone, the transit service lost over $800,000, or $8.5 million in 2022. As a result of the strike in Indianapolis, the mayor of Indianapolis at the time hoped to make some changes to the transportation system in Indianapolis. These potential changes included reserving the right-hand lane for transit and emergency vehicles, eliminating zone checks to speed up the boarding process, and selling tokens for 8 tokens for $1 to decrease the price and eliminate the use of cash on transit. He wanted to do this to improve the transit system and eliminate automobiles on the streets. “Sometimes, when the sickness is acute, the doctor has to prescribe pretty tough medicine and everyone knows our traffic sickness is serious.”

Cities across the country are also experiencing streetcar strikes. Transit strikes required people to walk to work and their destinations. Employees sought wage increases, which was the cause of the strikes. Some strikes lasted longer than others, and some affected more riders than others. The cities that had strikes included: Little Rock, Arkansas; Los Angeles, California; Washington D.C.; North Little Rock, Arkansas; Scranton, Pennsylvania; Buffalo, New York; and Niagara Falls, New York. In Los Angeles and St. Louis, the strikes were severe and left hundreds of thousands without transportation, and caused major traffic jams on streets that were not designed to handle such large automobile traffic amounts. Due to the number of transit strikes around the country, wages had to start rising, which led to less profit for the transit companies. This loss of profit led to the decrease of service of the streetcar in order to counteract those losses.

Decrease of service

The most reliable form of transportation was streetcars on tracks. “It was the passing of the classic streetcar, or electric trolley on tracks, that we regret. It was a very dependable and satisfying vehicle, rather symbolic of its times, we always thought.” The streetcar went to rest with the horse and buggy, as the cartoon in Figure 7 shows. After 100 years of operation, the final run of the streetcar was in 1953 and the streetcar had a banner that said: “Streetcar Named Expire” which imitated a movie in the time called “Streetcar Named Desire.” Opposed to the streetcar’s heyday, there was not as strong of a connection between people and the streetcar anymore, and this was a contributing factor in its demise. Immediately after the service of the streetcar was discontinued, tracks were removed from the streets around the city. In 1955, several neighborhoods across Indianapolis began removing all infrastructure to support the streetcar and replaced it with bus infrastructure. Beech Grove lines were removed and replaced by bus lines. Streetcar infrastructure was removed on College Avenue leading to Broad Ripple. Later, College Avenue was void of all signs of the streetcar and was strictly used for vehicular traffic. Streetcar tracks were pulled out across the city, and dumped in an empty field, depicted in Figure 6. When people discovered forgotten tracks, they were immediately reported and paved over, as if streetcars never existed. The city of Indianapolis once had several companies running streetcars, but as companies began to condense their business and abandon lines, this decreased service, decreased ridership, and ultimately led to a decline in the operation of the streetcar.

In the 1950s while streetcars were still in operation, Indianapolis had a much higher population density, with 7,700 people per square mile. This population density began to decline because the city limits sprawled to be almost 7 times bigger as of 2022 than it was in 1950, and the city-county has incorporated land that is undeveloped. When this land is eventually developed, it is being developed in a post-WWII way without the street grid and with sprawl because of the zoning codes that are put into place. As population density decreased, ridership did the same. The transit system in Indianapolis would have fewer routes, fewer drivers, and fewer vehicles, and less of the city would be covered because of the revamping of its services. Some areas of the city would “have to do without” when they once had public transit going through their area.

Indianapolis was not the only city shutting down streetcar service– there were several cities across the United States terminating service or making it difficult for streetcars to continue operating. Milwaukee started transitioning all transit to buses and stopped purchasing streetcars in 1955. In 1958, Houston, Texas made operating streetcars difficult to keep by adding a reduction of noise in its ordinances. While there were not any streetcars in Houston before this, this ordinance made it illegal to implement streetcars in the city of Houston.

Transit companies became too greedy by overselling tickets than there were seats or even holding straps. The Indianapolis Transit System increased fares due to low-profit margins. In comparison to some other cities around Indiana, it was still less expensive. Though this fare increase would not affect over half of the riders, the student passengers would be impacted and that is a large portion of passengers. Raising fares and decreasing the quality and quantity of service was another way that the streetcar declined. In 1955, The Indianapolis News said that the transit system was very slow, outdated, challenging to keep on the line, inconvenient, not comparable to other systems, and not as good as it once was. The idea of paying for riding in different zones causes friction between passengers, is costly for printing, and is timely for the driver and passengers. The newspaper article said that the transit companies should not be contracting out work, instead, they should be doing everything themselves to increase profits. Soon, the city of Indianapolis cooperated with the transit company less and less because it was not benefitting the city as much anymore and buses and cars were the next best thing to invest in.

Technological advances and the rise of the automobile

Personal transportation caused the end of the streetcar and trolley because of its “carpool, with its door-to-door pickup and delivery.” The downfall of public transportation was because of “(making) too many people too uncomfortable too often to last” and therefore people began using automobiles to get from place to place. As technology advanced and people were able to do things on their own, they started to prefer the convenience and style of a personal car. This caused an issue with traffic, and was not solved with public transportation because there was not a separate lane for transit, so it added to this traffic congestion. The Indianapolis News reported that automobile traffic got increasingly worse in Indianapolis. There were more accidents and it took people a long time to get to work, whether riding transit or in a car because the traffic was not separated. Cities across the country were facing this same issue as cars were becoming more popular amongst the general population. Transit companies at this point are less financially stable than they were during the Great Depression, and very few transit companies have been able to operate in the black since the war. Occupying the same amount of space, cars can carry 7 people and buses would carry 50 people. “While 2,600 passengers per hour can be carried on a single lane of an expressway, a right of way of similar width used for rapid transit trains can handle 60,000 passengers per hour.” Solving the traffic congestion would require a large capital investment and long-range planning to design more efficient roads. This would all ease the traffic problem as well as expand the economy by getting people and deliveries to their destinations faster.

As cities become more dense and developed, automobile traffic will continue to get more congested. In Los Angeles, the city is surrounded on three sides by highways, but there are still major traffic congestion issues. In an effort to coexist with automobiles, the Indianapolis Transit Company pushed for park and ride services. This would put parking lots in the outskirts of the city where people could park and ride transit into the city center, which would resolve much of the inner city traffic congestion. This would also solve the lack of parking in the downtown area because the transportation carries 60,000 passengers, while there were only 14,500 parking spaces in the mile square downtown. This solution of park and ride services was an idea from the Downtown Idea Exchange on how to improve ridership with the rise of the automobile.

The rise of the autobus

The good and bad of the bus system

With the downfall of the streetcars came the rise of the fuel-powered bus. At this time, the transit authority rebranded from Indianapolis Railways to the Indianapolis Transit System when there were no longer rails in use. The bus still operates as the only mode of public transportation in Indianapolis in 2022. In the early era of buses in Indianapolis, three private companies ran buses in Indianapolis. These buses had strict guidelines to follow because of streetcar service, and could only run on routes that did not have streetcar service. “Buses went mostly to outlying areas, streetcars to densely populated areas.” Buses became more popular in the city of Indianapolis during the middle of the 1950s. Using buses instead of streetcars made for profitable service for the transit authority in the City of Indianapolis compared to the level of profits during streetcar operation.

However, buses were not as efficient as they seemed on paper. They provided less frequent and consistent service than the streetcar and required fuel, something that the streetcar did not require. This made them expensive to operate, but were the preferred option to the streetcar because of the ability to move off of tracks and the larger carrying capacity. Passengers complained about the inconsistency of the schedule, smoothness of the ride, fumes, and the speed of service.

Today’s bus transportation system

Since the 1950s, the bus has been the only mode of public transportation in Indianapolis. In 2019, Indianapolis upgraded its bus system to a bus rapid transit system and currently has one line in operation, and is working on two additional lines. Busses were well used throughout the second half of the 20th century until the “transit company announced it was going out of business, and the administration of Mayor Richard Lugar created the Indianapolis Public Transportation Corporation to acquire the bus assets and operate a publicly subsidized Metro system” and bus ridership through IndyGo has declined steadily since then.

Public transportation in Indianapolis is controversial as some think that the city should not invest in something that does not operate to its full potential, while others think that the city should invest more in public transportation in order to improve it. Even throughout the late 20th century, people thought that the bus system was inadequate for the large population that Indianapolis had. Busses had low ridership, although it was promised that buses would provide better service and have higher ridership than the streetcar.

Transportation recommendations for the future

Transportation throughout the last two centuries has ebbed and flowed, but the future of transportation holds the potential to connect people intercontinentally, efficiently, and inexpensively. Cities across the country are beginning to rethink transit systems because of the traffic congestion and rise of gas prices. Many different planning and transportation organizations provided recommendations on how to improve transportation, including the Downtown Idea Exchange, Urban Land Institute, and precedents that other cities around the country have set in the public transit industry because “no large city the size of Indianapolis can exist without public transportation service.” The first complaint that citizens of Indianapolis had against the transit systems was that they were designed by people who lived out of state, and therefore they were not designed for the residents and did not fulfill the needs of the city.

The Indianapolis Star says that public transit must come back but it has to be of higher quality than it was before in order for people to use it. The biggest critique is that transit should be publicized in order to make it profitable. This would allow all passengers to ride for free, as tax money would pay for the transit systems. Public transportation would act as a public utility that residents would pay for like their gas or electricity, and it would be free to ride because they already paid for it with taxes. This would also encourage more people to leave their personal vehicles at home and utilize public transit, which would save users money without paying for gas and parking as well as solve the traffic congestion. Though privatizing transit in cities would solve the problem of money loss in the transit industry, it would also cause many problems and is also on the decline in other cities. If cities provided their own transit, it would provide a greater service to the community without price gouging.

The Urban Land Institute described several recommendations in 1957 to improve public transportation service in Indianapolis. First, transit vehicles must have their own designated lane in order to avoid automobile traffic. Second, stops should be about every 650 feet and these stops must be maintained. Third, fringe parking will increase ridership. Transit companies are losing money due to low ridership. The ridership is especially low during bad weather, vacations, and when commercial activity is decreased. Next, have an express service and a special event service to relieve heavier traffic during times with many events downtown. Additionally, improving facilities and vehicles will improve the transit system. In 1955, The Transit System decided to make the bus that would be servicing railroad officials more aesthetically pleasing by painting the bus with brighter colors. They decided that passengers and conductors would be happier to ride transit if it was more interesting to look at, and more comfortable to sit on, so they made a move to paint at least one bus on each line with bright colors. The Indianapolis News said “Maintenance of adequate mass transportation is essential to the healthy growth of this community.” The transit company should restrict cab service along transit lines. Next, staggering work hours will reduce congestion, as would eliminating on-street parking during peak hours on main arterial streets downtown to prevent interfering with public transit.

Of course, some argue that the “best prospect to turn the transportation tide is a high-speed monorail system.” Both the Indianapolis News and the Indianapolis Star report that high-speed trains would be the most efficient mode of transportation. “The use of rapid transit trains would substitute a little over 650 trains to do the job of 21 million autos– and they would require less than 1/20th of the one-way traffic lanes.” The cities of Cleveland, Chicago, and Philadelphia all had great models of transit systems during the busing era, proving that a city could operate efficiently with high-speed trains. However, city officials in 1956 in Indianapolis said that they did not believe that high-speed trains would help the traffic issue because it did not help the traffic issues in Chicago.

CASE STUDY

Fountain Square: The rise and fall of an Indianapolis streetcar suburb

With the advent of the streetcar in Indianapolis came the streetcar suburb. Streetcar suburbs were master-planned communities that were located on streetcar lines and were further outside of the city center. These communities had access to local amenities so that residents did not have to travel to get basic necessities. These communities consisted of diverse populations as streetcars had riders of all socioeconomic classes, ages, and races. The “golden age” of the streetcar was from 1900 to 1925, when the streetcar reached ‘streetcar suburbs.’ These suburbs were located on the outskirts of Indianapolis at the time, and included neighborhoods like Emerson Heights, Irvington, Broad Ripple, Zionsville, and Fountain Square. Broad Ripple Village grew as a neighborhood because of the streetcar service. Streetcars allowed Broad Ripple to be connected to downtown Indianapolis and led to its growth, making it a “streetcar suburb.” Zionsville, a city northwest of Indianapolis, grew because of interurban transportation to and from Indianapolis. Features of streetcar suburbs included “stone curbs, sidewalk placement, lot size and the placement of houses on their lots” and dominant east-west streets for easy access to trolley stops. These features made the streetcar suburbs highly sought after for living and traveling because it was easy to walk to amenities and they were safe neighborhoods because of the constant eyes on the streets.

Fountain Square is an original streetcar suburb of Indianapolis and is still prosperous today. It is a commercial district on the southside of Indianapolis, and at one time was considered “the end” of the Virginia Avenue streetcar line and was also a place for the streetcars to turn around. The neighborhood grew as the streetcar line took residents to and from downtown Indianapolis. Fountain Square was located in a great place for transportation in Indianapolis. It had Virginia Avenue, which was one of the streets that were part of the original ‘mile square’ and was also a “focal point of the street railway system in the city.” The area also connected Shelbyville to Indianapolis. Fountain Square was home to one of the first tracks in the streetcar system and even got an extension to its line in 1893. The streetcar system allowed Fountain Square to be “linked to downtown commerce.”

Streetcar suburbs grow as a community and residential neighborhood with residents and visitors because of the service that the streetcars provide the area. Fountain Square grew in the same way with streetcars bringing visitors and residents to and from the neighborhood and downtown Indianapolis. As Fountain Square grew, it became a popular spot for shopping and watching shows, especially. The neighborhood grew with churches, theaters, shops, schools, and homes within the first 30 years of the 20th century. Within 20 years at the beginning of the 1900s, 11 theaters were constructed to host shows and other performances and this created the character of the neighborhood.

This prosperity and character started to quickly decline when the streetcar left and the use of personal automobiles grew. Streetcars were replaced with motor buses in 1955. Around this time, automobile traffic grew in the neighborhood, and the neighborhood’s beloved fountain was relocated to Garfield Park due to traffic congestion in 1954. Theaters, which made the personality of the neighborhood, began closing around the time that the trolley was removed, and the neighborhood lost its liveliness. During the 1950s, the streetcar declined across the city, but Fountain Square was hit especially hard when it stopped servicing the neighborhood. When Interstates 65 and 70 started construction, tens of thousands of families across the city were displaced, including in Fountain Square. People started moving out of the neighborhood and stopped shopping and supporting its economy, and many buildings became vacant.

Public transportation, specifically the streetcar, is a necessary portal to bring people to and from places of commerce and to grow neighborhoods and economies. This is proven in many different places across the city of Indianapolis, but especially in Fountain Square. Today, Fountain Square is located on the city’s bus rapid transit system route and is thriving as it connects to downtown Indianapolis, Greenwood, and Broad Ripple.

CONCLUSION

The city of Indianapolis was proven to be the “Crossroads of America” with its robust transit system throughout the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The transportation options began with the mule car and are now using a bus rapid transit system to get around. During the middle of the twentieth century, the transit option was the streetcar, which ran on tracks and attached to a line. The streetcar was the way that women could go to shops downtown while their husbands got to work on the streetcar and returned home at the end of the day. Streetcars solved traffic problems and were an efficient way to move people quickly and inexpensively. When the streetcar declined, traffic increased, and the economy was impacted negatively. The bus seemed to be the new and better option at the time, but caused other problems and decreased service that was in place from the streetcar era. This study used historical newspapers from the streetcar era and journals with opinions from today’s city planners and transportation professionals on the streetcars and buses of the past.

References:

“A Streetcar Named Expire.” 2019. Indianapolis Business Journal 11 (40): 6A.

“Fountain Square - Fountain Square Indy.” n.d. Fountain Square Theatre. Accessed November, 2022. http://www.fountainsquareindy.com/about-us/fountain-square/.

“Indianapolis Streetcars - 1923.” n.d. Chicago Transit & Railfan. http://www.chicagorailfan.com/bcind23t.html.

“Retro Indy: Interurban streetcars of the early 1900s.” 2014. IndyStar. https://www.indystar.com/story/news/history/retroindy/2014/01/17/interurban-streetcars-retroindy/4583215/.

Bodenhamer, David, and Robert Barrows. 1994. The Encyclopedia of Indianapolis. Bloomington and Indianapolis, Indiana: Indiana University Press.

Bowman, Anna. 2022. “The history of streetcars in Indianapolis, IN.” INDYtoday. https://indytoday.6amcity.com/the-history-of-streetcars-indianapolis-in.

Copeland, Tashi. 2022. “Public Transit is More than a Bus Line—it can be a Lifeline.” Central Indiana Community Foundation. https://www.cicf.org/2022/08/15/public-transit-is-more-than-a-bus-line-it-can-be-a-lifeline/.

Diebold, Paul C. 2009. “Emerson Avenue Addition Historic District, Indianapolis City, Marion County, Indianapolis, IN, 46219.” LivingPlaces. https://www.livingplaces.com/IN/Marion_County/Indianapolis_City/Emerson_Avenue_Addition_Historic_District.html.

Glass, James. 2019. “A lesson in Indy's transportation history: 'We have come full circle.'” IndyStar (Indianapolis), February 3, 2019. https://www.indystar.com/story/opinion/2019/02/03/james-glass-lesson-indys-transportation-history-we-have-come-full-circle/2748776002/.

Hamlett, Ryan. 2013. “Reminders of Indy's Transit Past.” Historic Indianapolis. https://historicindianapolis.com/reminders-of-indys-transit-past/.

Heritage Rail Alliance. n.d. “Trolley Museum Collection | Indiana Interurbans, Streetcars & Mule Cars — Hoosier Heartland Trolley Co.” Hoosier Heartland Trolley Co. https://www.hoosiertrolley.org/collection-trolleys/#Top.

Hoosier History Live. 2013. “Interurbans: Their rise and fall across Indiana.” Hoosier History Live. https://hoosierhistorylive.org/mail/2013-09-28.html.

Hoover, Gary. 2019. “High Speed Electric Rail Comes to Indiana – 122 Years Ago - Business History.” The American Business History Center. https://americanbusinesshistory.org/high-speed-electric-rail-comes-to-indiana-122-years-ago/.

Indianapolis Historic Preservation Commission. 1984. “Historic Area Preservation Plan Fountain Square.” AWS. https://citybase-cms-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/94be9a6e6b554681b3ccc502827fe8e7.pdf.

Indiana-University Purdue University Indianapolis. n.d. “Fountain Square – The Polis Center.” The Polis Center. https://polis.iupui.edu/about/community-culture/project-on-religion-culture/study-neighborhoods/fountain-square/.

Johnson, Charles, and Jake Sheff. n.d. “Buses - indyencyclopedia.org.” Encyclopedia of Indianapolis. https://indyencyclopedia.org/buses/.

Johnson, Charles. 1994. “Streetcars - indyencyclopedia.org.” Encyclopedia of Indianapolis. https://indyencyclopedia.org/streetcars/.

Lorenzo, Blair, and William Zion. 2020. “Urban Fragments in a Sea of Suburbs: Three Neighborhoods in Indianapolis.” The Fox and the City. https://thefoxandthecity.com/articles/urban-fragments-sea-suburbs-three-neighborhoods-indianapolis.

Marlette, Jerry. n.d. “Interurbans - indyencyclopedia.org.” Encyclopedia of Indianapolis. https://indyencyclopedia.org/interurbans/.

Nichols, Cameron. 2018. “Electrifying Indianapolis' Streetcar System for the 20th Century — Hoosier Heartland Trolley Co.” Hoosier Heartland Trolley Co. https://www.hoosiertrolley.org/live-wire-blog-1/electrification-indianapolis-street-railways.

Planetizen. n.d. “What Are Streetcar Suburbs?” Planopedia. https://www.planetizen.com/definition/streetcar-suburbs.

Race, Bruce. 2013. “Our Streetcar Legacy: High-Value Neighborhoods.” Indianapolis Business Journal 50:33.

Simpson, Richard M. 2020. “Indianapolis Street Car Saturday – Getting to Irvington – Indiana Transportation History.” Indiana Transportation History. https://intransporthistory.home.blog/2020/06/20/indianapolis-street-car-saturday-getting-to-irvington/.

Swift, Fred. 2017. “Looking back at the history of public transportation.” Hamilton County Reporter. https://readthereporter.com/looking-back-at-the-history-of-public-transportation/.

The Indianapolis News. 1955. “Beech Grove, English Lines to be Moved.” January 20, 1955, 39. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/111024498/1201955-beech-grove-english-lines-to/.

The Indianapolis News. 1955. “Come, Let Us Travel Together the Trail Known as Memory Lane.” August 8, 1955, 8. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/110523801/08081955-come-let-us-travel-together/.

The Indianapolis News. 1955. “Indianapolis Transit System, Inc.” January 3, 1955, 30. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/110996320/1031955-indianapolis-transit-system-in/.

The Indianapolis News. 1955. “Is Private Transit Doomed in Cities?” October 20, 1955, 11. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/111211431/10201955-is-private-transit-doomed-in/.

The Indianapolis News. 1955. “L.A. Transit Lines Tied Up.” June 20, 1955, 26. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/110519850/06201955-la-transit-lines-tied-up/.

The Indianapolis News. 1955. “Let’s not bury it alive.” August 8, 1955, 17. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/111203415/881955-lets-not-bury-it-alive/.

The Indianapolis News. 1955. “Modernize Transit Operations to Get Out of Red and Into Black.” July 22, 1955, 8. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/111153914/7221955-modernize-transit-operations-t/.

The Indianapolis News. 1955. “Motorists No Longer Avoid College Avenue.” August 23, 1955, 27. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/110524781/8231955-motorists-no-longer-avoid-coll/.

The Indianapolis News. 1955. “No, You’re Not Off Your Trolley.” September 22, 1955, 1. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/111209435/9221955-no-youre-not-off-your-trolle/.

The Indianapolis News. 1955. “Now It’s Trolleys that Miss the Bus.” August 4, 1955, 52. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/110522574/841955-now-its-trolleys-that-miss-th/.

The Indianapolis News. 1955. “Progress Takes its Toll.” July 20, 1955, 10. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/110520759/7201955-progress-takes-its-toll-cartoo/.

The Indianapolis News. 1955. “The Biggest 20 cents worth in Indianapolis.” February 14, 1955. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/111113684/2141955-the-biggest-20-cents-worth-in/.

The Indianapolis News. 1955. “The Indianapolis Transit System’s overhead signs….” April 6, 1955, 29. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/111148897/461955-the-indianapolis-transit-system/.

The Indianapolis News. 1955. “Trackless Trolleys on Way Out.” December 5, 1955, 1. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/110530251/1231955-trackless-trolleys-on-way-out/.

The Indianapolis News. 1955. “Traffic Jam Paralyzes Strikebound St. Louis.” October 11, 1955, 1. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/110528412/10111955-traffic-jam-paralyzes-strikeb/.

The Indianapolis News. 1955. “Transit Revenues Skid as Traffic Problem Grows.” February 3, 1955, 29. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/112192171/02031955-transit-revenues-skid-as-traf/.

The Indianapolis News. 1955. “Transit Study Offers Solution to Reduce Losses.” July 19, 1955, 19. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/111152981/7191955-transit-study-offers-solution/.

The Indianapolis News. 1955. “Transit System Pushing Fringe Area Parking.” March 14, 1955, 29. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/111147743/3141955-transit-system-pushing-fringe/.

The Indianapolis News. 1955. “Trolley Wires to Come Down on College.” February 25, 1955, 19. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/110517710/02251955-trolley-wires-on-college-to-c/.

The Indianapolis News. 1955. “What else do we get besides “A” for effort?” March 7, 1955, 5. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/111146666/371955-what-else-do-we-get-besides-a-f/.

The Indianapolis News. 1955. “What else do we get besides “A” for effort?” March 7, 1955, 5. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/111146666/371955-what-else-do-we-get-besides-a-f/.

The Indianapolis News. 1956. “Toward Better Transportation.” February 18, 1956, 6. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/111377173/2181956-toward-better-transportation/.

The Indianapolis News. 1957. “Better Service With Fewer Buses and Routes Promised.” January 30, 1957, 12. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/111390383/1301957-better-service-with-fewer-buse/.

The Indianapolis News. 1957. “Complaints on Buses as Varied as the Passengers.” April 4, 1957, 1. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/110540350/4041957-complaints-on-buses-as-varied/.

The Indianapolis News. 1957. “Indianapolis Transit System.” August 10, 1957, 12. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/110542773/8101957-indianapolis-transit-system/.

The Indianapolis News. 1957. “Old Trolleys Never Die.” March 19, 1957, 12. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/111391086/3191957-old-trolleys-never-die/.

The Indianapolis News. 1957. “PSC Approves Finance Plan for Bus Purchases.” January 12, 1957, 1. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/111388880/1121957-psc-approves-finance-plan-for/.

The Indianapolis News. 1957. “Streetcar Named Desire for Tourists.” June 25, 1957, 3. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/110541131/6251957-streetcar-named-desire-for-tou/.

The Indianapolis News. 1957. “Suggestions for Improving Bus Patronage.” October 24, 1957, 9. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/111394003/10241957-suggestions-for-improving-bus/.

The Indianapolis News. 1957. “Transit Firm to Revamp and Expand Service.” January 24, 1957, 1. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/111389771/1241957-transit-firm-to-revamp-and-exp/.

The Indianapolis News. 1958. “America’s Best Comics.” August 29, 1958, 18. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/110818820/8291958-americas-best-comics/.

The Indianapolis News. 1958. “Nashville People Like Bus Service.” December 23, 1958, 7. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/110852711/12231958-nashville-people-like-bus-ser/.

The Indianapolis News. 1958. “Time to Wake Up.” May 10, 1958, 13. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/110554969/5101958-time-to-wake-up/.

The Indianapolis News. 1958. “Well, Lookee Here!” June 26, 1958, 28. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/110806993/6261958-well-lookee-here/.

The Indianapolis News. 1959. “Cost of Transfers Would Go Up to 5c.” August 6, 1959, 1. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/111437383/861959-cost-of-transfers-would-go-up-t/.

The Indianapolis News. 1959. “Old Trolley Clanged and Tooted.” May 7, 1959, 13. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/111797518/5071959-old-trolley-clanged-and-tooted/.

The Indianapolis News. 1959. “Traction Car Exhibit in City Park Asked.” February 4, 1959, 13. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/110827519/241959-traction-car-exhibit-in-city-pa/.

The Indianapolis News. 1959. “Traffic Problem Growing Worse.” June 15, 1959, 1. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/111825450/6151959-traffic-problem-growing-worse/.

The Indianapolis News. 1960. “City Transit Services Reviving.” February 2, 1960, 2. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/111439039/221960-city-transit-services-reviving/.

The Indianapolis News. 1960. “No Change Made on Pupil, Transfer Cost.” January 22, 1960, 1. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/111438389/1221960-no-change-made-on-pupil-trans/.

The Indianapolis Star. 1955. “Pictures to Illustrate Interurban History Sought.” July 31, 1955, 74. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/110521267/7311955-pictures-to-illustrate-interur/.

The Indianapolis Star. 1955. “That Reminds Me.” January 1, 1955, 13. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/110514982/1011955-streetcar-strike/.

The Indianapolis Star. 1955. “The Things I Hear.” January 6, 1955, 21. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/112188823/01061955-the-things-i-hear/.

The Indianapolis Star. 1955. “Transit Firm, with '54 Loss, Not to Ask Fare Increase.” April 1, 1955, 24. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/110519188/04011955-transit-firm-with-54-loss/.

The Indianapolis Star. 1955. “Transit Industry Takes Own Busses for a Ride.” December 9, 1955, 39. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/110532373/1291955-transit-industry-takes-own-bus/.

The Indianapolis Star. 1955. “Transit Strikes Grip 7 Cities Over Nation.” July 10, 1955, 11. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/110520259/7101955-transit-strikes-grip-7-cities/.

The Indianapolis Star. 1955. “Transit System Seeks New Services.” January 16, 1955, 50. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/111017810/1161955-transit-system-seeks-new-servi/.

The Indianapolis Star. 1955. “Trolley Rider Kicks.” October 29, 1955, 16. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/111231470/10291955-trolley-rider-kicks/.

The Indianapolis Star. 1955. “We have a lot to Keep us Busy in our Leisure Time.” March 31, 1955, 20. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/110518506/03311955-we-have-a-lot-to-keep-us-busy/.

The Indianapolis Star. 1956. “Bayt Seeks To Lower Fares, Too.” February 16, 1956, 1. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/111388193/2161956-bayt-seeks-to-lower-fares-too/.

The Indianapolis Star. 1956. “Indianapolis Transit to Push New Services.” January 1, 1956, 84. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/110533738/1011956-indianapolis-transit-to-push-n/.

The Indianapolis Star. 1956. “Since 1864 This Man Spells ‘Business.’” January 1, 1956, 76. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/110534087/1011956-since-1864-this-man-spells-bus/.

The Indianapolis Star. 1956. “Speeded Up Suburban Flow a Traffic Must.” March 11, 1956, 22. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/110535862/3111956-speeded-up-suburban-flow-a-tra/.

The Indianapolis Star. 1956. “U.S. To Urge ‘Voluntary’ Integration.” December 11, 1956, 4. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/110538583/12111956-us-to-urge-voluntary-integrat/.

The Indianapolis Star. 1957. “The Things I Hear.” March 8, 1957, 27. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/110539979/381957-the-things-i-hear/.

The Indianapolis Star. 1957. “Transit System Failures Plague Cities of Today.” September 4, 1957, 1. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/110543646/941957-transit-system-failures-plague/.

The Indianapolis Star. 1957. “Why Worry? We Are Ready for Trouble.” January 16, 1957, 12. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/110539480/1161957-why-worry-we-are-ready-for-tr/.

The Indianapolis Star. 1958. “Auto Show Proves We’ve Come a Long Way.” January 24, 1958, 12. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/110550997/1241958-auto-show-proves-weve-come-a/.

The Indianapolis Star. 1958. “Back When.” September 21, 1958, 119. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/110823166/9211958-back-when/.

The Indianapolis Star. 1958. “End of an Era Isn’t Always Occasion for Mourning.” June 24, 1958, 14. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/110556462/6241958-end-of-era-isnt-always-occasi/.

The Indianapolis Star. 1958. “Memo for Next Meeting of Straphanger’s Club.” December 8, 1958, 16. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/110826104/1281958-memo-for-next-meeting-of-strap/.

The Indianapolis Star. 1958. “Parking Ban Proposed to Aid Busses.” February 15, 1958, 5. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/111395117/2151958-parking-ban-proposed-to-aid-bu/.

The Indianapolis Star. 1958. “People Who Ride Busses Get More Exercise.” March 29, 1958, 12. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/110554344/3291958-people-who-ride-busses-get-mor/.

The Indianapolis Star. 1958. “Whose Side They On?” January 31, 1958, 14. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/110552278/1311958-whose-side-they-on/.

The Indianapolis Star. 1960. “Classic Streetcar was Symbol of Its Era.” August 22, 1960, 12. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/111679873/8221960-classic-streetcar-was-symbol-o/.

The Polis Center. n.d. “Fountain Square Neighborhood Timeline.” IUPUI archives. Accessed November 29, 2022. https://archives.iupui.edu/bitstream/handle/2450/5905/FountainSquare.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

Tranfield, Pamela. 1999. “Indiana Interurban and Indianapolis Streetcar Photographs, CA. 1912-CA. 1926.” Indiana Historical Society. https://indianahistory.org/wp-content/uploads/indiana-interurban-and-indianapolis-streetcar.pdf.